Some thoughts on Elysium show by Graham Hartill

Some thoughts on Elysium show by Graham Hartill

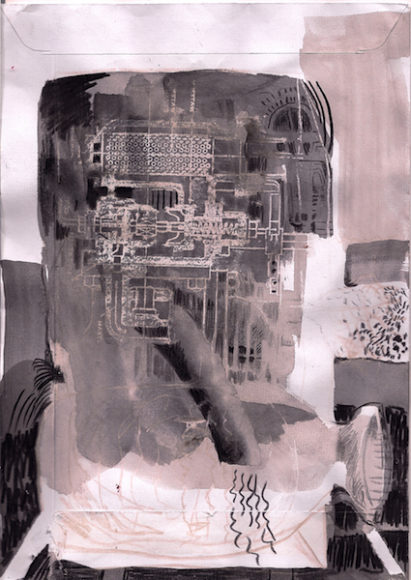

What else could represent so clearly the idea of spirit, mind, soul, whilst remaining so incorrigibly and bafflingly, a material object? – writes the artist. Bafflingly? I’m grateful to Penny for drawing my attention to this word, its etymology pointing to implications of disgrace and vilification, scoffing; the Norman French ‘baffer’ meant, apparently, ‘to slap in the face’. A baffle is something that changes the course of something, a thought perhaps, or an energy flow. We look at a head, particularly a face, for recognition of an other’s self, of course, but as these paintings indicate, a head may be more akin to a helmet or mask, than to a transcription or emblem of its bearer’s actual life experience. Either way, it’s what we see, what we make, of another, on first encounter at least.

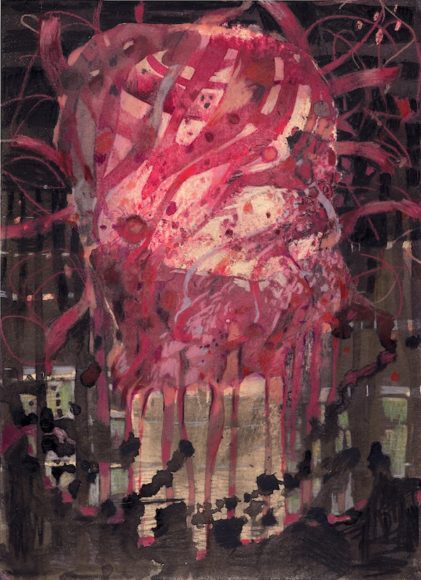

What cultures down the ages have certainly realized is that the head is a locus of power, both spiritual and material; in fact, the head can be seen as the ultimate embodiment of the truth that, to quote the American social theorist Ernest Becker, all power is sacred power; there’s more than an element of ritual sacrifice in the beheading of a king or criminal, or the toppling of a tyrant’s statue, noosed, like Saddam’s or Stalin’s.

It’s not just in the heart of colonial darkness that men have gone head-hunting – it happens in Canary Wharf and Cardiff, and wherever the paparazzi ply their trade. The Society of the Spectacle is a world of recognitions and reflections. It is a metaphor that reaches back to the myth of Osiris and beyond, that is caught in the story of Orpheus, whose severed head went floating down the stream, still singing, just like Elvis’s. The corn god rises to meet his beheading, just like Jesus, caught in Bosch’s painting, still amongst a swirl of animal appetites. Culture depends on this.

We put on our masks with the growth of what we call our personalities, and shape them throughout our lives, or try to; we survive perhaps to the extent that we succeed. Someone said that by 50 or so we’ve all got the masks that we deserve. When, as children, we learn to differentiate I from Other, when we create our first strong subjectivity, our first sentence in fact, which is our striving to act in the world, our first self-consciousness, then we see our heads, our faces, in the world’s reflection. Thus can the head, like Orpheus’s, be regarded as synonymous with utterance. And of course if someone is silent, then it is baffling, fascinating: What are they thinking – of us perhaps? Or what are they dreaming? – which none of us, not even the dreamer herself can understand – see for example Odilon Redon’s dreaming, floating heads.

Penny’s paintings toss up a carnival of mental states or dramas. For me they question any distinction we habitually make between biology, spirit and social power. They come from the same considerations that I suspect she encounters working as a therapist, using art as a space of encounter between participants, some of whom struggle with verbal expression. We see images of dismemberment, of warfare, secrecy, encounters and imprisonments; veils, masks, pedestals, curtains, helmets. For me the idea that any picture holds a mirror up to ourselves is made explicit; all of these heads are mine, living out my life in that peculiarly human state of knowing my self, my face, and what I am – an animal with self-consciousness – from which I make my theatre.

5 October 2009

Graham Hartill’s selected poems, Cennau’s Bell was published in 2005 by the Collective Press and 2007 saw the launch of A Winged Head by Parthian Books). He is Writer in Residence at HMP Parc, Bridgend and teaches creative writing for therapeutic purposes at Bristol University.

email: graham.hartill@tiscali.co.uk

http://www.academi.org/list-of-writers/i/129683/

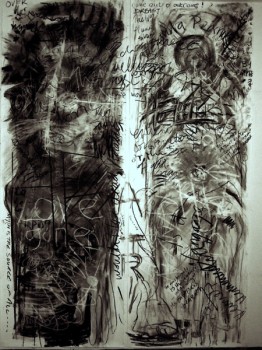

During the morning, artist Penny Hallas had created two drawings for the Border/Lines event in her studio upstairs, and people were taken one by one to the studio to record their pre-prepared responses to the Blanchot essay to camera. After each reading the guest was invited to change both drawings, one with a rubber and one with a piece of charcoal. When everyone had done this, people came together to improvise written responses to the day, creating brief sentences and word-patterns which were then torn in half, each part of the sentence acquiring a response and a completion by another of the participants.?Armed with these reconstituted sentences the participants returned to the studio where, with the use again of rubber and charcoal, they performed a mass intervention on the drawings.

During the morning, artist Penny Hallas had created two drawings for the Border/Lines event in her studio upstairs, and people were taken one by one to the studio to record their pre-prepared responses to the Blanchot essay to camera. After each reading the guest was invited to change both drawings, one with a rubber and one with a piece of charcoal. When everyone had done this, people came together to improvise written responses to the day, creating brief sentences and word-patterns which were then torn in half, each part of the sentence acquiring a response and a completion by another of the participants.?Armed with these reconstituted sentences the participants returned to the studio where, with the use again of rubber and charcoal, they performed a mass intervention on the drawings.

Some thoughts on Elysium show by Graham Hartill

Some thoughts on Elysium show by Graham Hartill